Logical fallacies — those logical gaps that invalidate arguments — don’t appear to be always easy to spot.

While some come inside the kind of loud, obvious inconsistencies, others can merely fly beneath the radar, sneaking into regularly meetings and conversations undetected.

Our data on logical fallacies will imply you’ll be able to assemble upper arguments and decide logical missteps.

Jump to:

- What a logical fallacy is

- Formal vs. casual fallacies

- Straw guy fallacy

- Correlation/causation fallacy

- Advert hominem fallacy

What’s a logical fallacy?

Logical fallacies are deceptive or false arguments that may seem stronger than they actually are on account of psychological persuasion, on the other hand are showed incorrect with reasoning and further examination.

The ones mistakes in reasoning normally surround a topic and a premise that doesn’t support the realization. There are two types of fallacies: formal and informal.

- Formal: Formal fallacies are arguments that have invalid building, form, or context errors.

- Informal: Informal fallacies are arguments that have beside the point or unsuitable premises.

Having an understanding of fundamental logical fallacies will let you further confidently parse the arguments and claims you’re taking section in and witness on a daily basis — conserving aside fact from sharply dressed fiction.

15 Not unusual Logical Fallacies

1. The Straw Man Fallacy

This fallacy occurs when your opponent over-simplifies or misrepresents your argument (i.e., setting up a “straw man”) to let you attack or refute. Instead of utterly addressing your precise argument, audio gadget relying on this fallacy supply a superficially an an identical — on the other hand in any case now not an identical — fashion of your precise stance, helping them create the illusion of merely defeating you.

Example:

John: I consider we should hire any person to redesign our web page.

Lola: You might be announcing we should throw our money away on external resources instead of organising up our in-house design team of workers? This is going to hurt our company in any case.

2. The Bandwagon Fallacy

Just because the most important population of people imagine a proposition is true, does no longer mechanically make it true. Recognition alone isn’t enough to validate a topic, even though it’s frequently used as a standalone justification of validity. Arguments in this style don’t consider whether or not or no longer or now not the population validating the argument is actually qualified to do so, or if reverse evidence exists.

While most people expect to see bandwagon arguments in selling (e.g., “3 out of four people assume X brand toothpaste cleans teeth very best”), this fallacy can merely sneak its approach into regularly meetings and conversations.

Example:

The majority of people imagine advertisers should spend more cash on billboards, so billboards are objectively the best form of business.

3. The Enchantment to Authority Fallacy

While appeals to authority are certainly not always flawed, they may be able to briefly turn into bad whilst you rely too carefully on the opinion of a single specific particular person — in particular if that specific particular person is attempting to validate something outside of their enjoy.

Getting knowledgeable decide to once more your proposition can be a tough addition to an present argument, on the other hand it can’t be the pillar all of your argument rests on. Just because any person able of power believes something to be true, does no longer make it true.

Example:

Although our This fall numbers are so much not up to usual, we should push forward using the equivalent methodology because of our CEO Barbara says this is the best approach.

4. The False Catch 22 situation Fallacy

This no longer bizarre fallacy misleads by way of presenting difficult issues with regards to two inherently adversarial facets. Instead of acknowledging that almost all (if now not all) issues may also be regarded as on a spectrum of possibilities and stances, the false predicament fallacy asserts that there are simplest two mutually distinctive effects.

This fallacy is particularly problematic because of it will lend false credence to over the top stances, ignoring possible choices for compromise or possibilities to re-frame the issue in a brand spanking new approach.

Example:

We will each imagine Barbara’s plan, or just let the problem fail. There’s no other selection.

5. The Hasty Generalization Fallacy

This fallacy occurs when any person draws expansive conclusions according to inadequate or insufficient evidence. In several words, they leap to conclusions regarding the validity of a proposition with some — on the other hand now not enough — evidence to once more it up, and omit potential counterarguments.

Example:

Two individuals of my team of workers have turn into further engaged employees after taking public speaking classes. That proves we should have vital public speaking classes for all of the company to give a boost to employee engagement.

6. The Slothful Induction Fallacy

Slothful induction is the proper inverse of the hasty generalization fallacy above. This fallacy occurs when sufficient logical evidence strongly indicates a particular conclusion is true, on the other hand any person fails to acknowledge it, instead attributing the outcome to twist of fate or something unrelated only.

Example:

Even though every problem Brad has managed throughout the ultimate two years has run approach behind agenda, I however assume we will chalk it up to unfortunate cases, now not his problem keep an eye on talents.

7. The Correlation/Causation Fallacy

If two problems appear to be correlated, this doesn’t necessarily indicate that a type of problems irrefutably introduced in regards to the reverse issue. This may most likely appear to be an obvious fallacy to spot, on the other hand it can be tricky to catch in practice — in particular whilst you truly wish to find a correlation between two problems of data to prove your stage.

Example:

Our blog views have been down in April. We moreover changed the color of our blog header in April. Which means that changing the color of the blog header led to fewer views in April.

8. The Anecdotal Evidence Fallacy

As a substitute of logical evidence, this fallacy substitutes examples from any person’s personal enjoy. Arguments that rely carefully on anecdotal evidence typically have a tendency to omit the fact that one (in all probability isolated) example can’t stand alone as definitive proof of a higher premise.

Example:

Thought to be one among our customers doubled their conversions after changing all their landing internet web page text to good purple. Therefore, changing all text to purple is a showed option to double conversions.

9. The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

This fallacy gets its vibrant name from an anecdote a couple of Texan who fires his gun at a barn wall, and then proceeds to paint a objective around the closest cluster of bullet holes. He then problems at the bullet-riddled objective as evidence of his an expert marksmanship.

Audio gadget who rely on the Texas sharpshooter fallacy typically have a tendency to cherry-pick data clusters according to a predetermined conclusion. Instead of letting a whole spectrum of evidence lead them to a logical conclusion, they to find patterns and correlations in support of their goals, and omit about evidence that contradicts them or suggests the clusters weren’t actually statistically necessary.

Example:

Lisa purchased her first startup to an influential tech company, so she will have to be a a success entrepreneur. (She ignores the fact that 4 of her startups have failed since then.)

10. The Center Ground Fallacy

This fallacy assumes {{that a}} compromise between two over the top conflicting problems is always true. Arguments of this style omit in regards to the chance that one or both one of the most extremes might be utterly true or false — rendering any form of compromise between the two invalid as neatly.

Example:

Lola thinks one of the most best possible tactics to give a boost to conversions is to redesign all the company web page, on the other hand John is firmly in opposition to creating any changes to the web page. Therefore, the best approach is to redesign some portions of the web page.

11. The Burden of Proof Fallacy

If a person claims that X is true, it’s their accountability to supply evidence in support of that remark. It’s invalid to claim that X is true until any person else can prove that X isn’t true. Similarly, it is also invalid to claim that X is true because of it’s unattainable to prove that X is faux.

In several words, just because there’s no evidence introduced in opposition to at least one factor, that doesn’t mechanically make that issue true.

Example:

Barbara believes the selling corporate’s place of job is haunted, since nobody has ever showed that it isn’t haunted.

12. The Non-public Incredulity Fallacy

If when you’ve got factor understanding how or why something is true, that doesn’t mechanically suggest the item in question is faux. A personal or collective ignorance isn’t enough to render a claim invalid.

Example:

I have no idea how redesigning our web page resulted in more conversions, so there will have to have been each and every different factor at play.

13. The “No True Scotsman” Fallacy

Frequently used to offer protection to assertions that rely on commonplace generalizations (like “all Marketers love pie”) this fallacy inaccurately deflects counterexamples to a claim by way of changing the site or conditions of the original claim to exclude the counterexample.

In several words, instead of acknowledging {{that a}} counterexample to their distinctive claim exists, the speaker amends the words of the claim. Inside the example beneath, when Barabara pieces a legitimate counterexample to John’s claim, John changes the words of his claim to exclude Barbara’s counterexample.

Example:

John: No marketer would ever put two call-to-actions on a single landing internet web page.

Barbara: Lola, a marketer, actually came upon great good fortune striking two call-to-actions on a single landing internet web page for our ultimate advertising and marketing marketing campaign.

John: Well, no true marketer would put two call-to-actions on a single landing internet web page, so Lola will have to now not be an actual marketer.

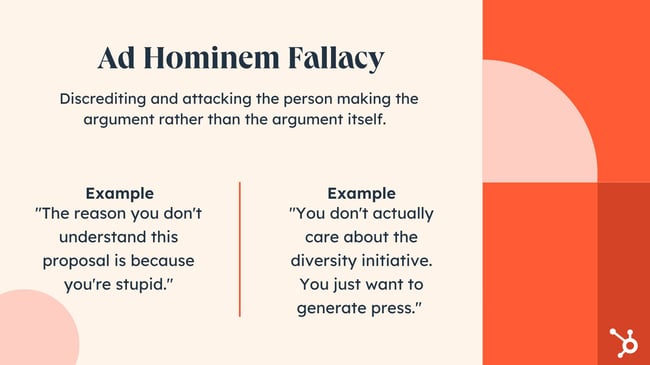

14. The Ad Hominem Fallacy

An ad hominem fallacy occurs whilst you attack any person individually moderately than using commonplace sense to refute their argument. Instead they’ll attack physically glance, personal traits, or other beside the point characteristics to criticize the other’s standpoint. The ones attacks can also be leveled at institutions or groups.

Example:

Barbara: We should overview the ones data gadgets all over again merely to make sure they’re right kind.

Tim: I figured you’ll be able to counsel that since you’re just a bit gradual in relation to math.

15. The Tu Quoque Fallacy

The tu quoque fallacy (Latin for “you moreover”) is an invalid attempt to discredit an opponent by way of answering criticism with criticism — on the other hand in no way actually presenting a counterargument to the original disputed claim.

Inside the example beneath, Lola makes a claim. Instead of presenting evidence against Lola’s claim, John levels a claim against Lola. This attack does no longer actually help John achieve proving Lola incorrect, since he does no longer maintain her distinctive claim in any capacity.

Example:

Lola: I don’t consider John generally is a good fit to control this problem, because of he does no longer have a lot of enjoy with problem keep an eye on.

John: Alternatively you do not need a lot of enjoy in problem keep an eye on each!

16. The Fallacy Fallacy

That is something necessary to keep in mind when sniffing out fallacies: just because any person’s argument is decided by way of a fallacy does no longer necessarily suggest that their claim is inherently untrue.

Making a fallacy-riddled claim does no longer mechanically invalidate the root of the argument — it merely approach the argument does no longer actually validate their premise. In several words, their argument sucks, on the other hand they aren’t necessarily incorrect.

Example:

John’s argument in make a choice of redesigning the company web page clearly relied carefully on cherry-picked statistics in support of his claim, so Lola decided that redesigning the web page will have to now not be a good resolution.

Recognize Logical Fallacies

Recognizing logical fallacies once they occur and studying simple easy methods to fight them will prove useful for navigating disputes in every personal {{and professional}} settings. We hope the ideas above will imply you’ll be able to avoid one of the most most no longer bizarre argument pitfals and benefit from commonplace sense instead.

This text was revealed in July 2018 and has been up-to-the-minute for comprehensiveness.

![]()

Contents

- 1 What’s a logical fallacy?

- 2 15 Not unusual Logical Fallacies

- 2.1 1. The Straw Man Fallacy

- 2.2 2. The Bandwagon Fallacy

- 2.3 3. The Enchantment to Authority Fallacy

- 2.4 4. The False Catch 22 situation Fallacy

- 2.5 5. The Hasty Generalization Fallacy

- 2.6 6. The Slothful Induction Fallacy

- 2.7 7. The Correlation/Causation Fallacy

- 2.8 8. The Anecdotal Evidence Fallacy

- 2.9 9. The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

- 2.10 10. The Center Ground Fallacy

- 2.11 11. The Burden of Proof Fallacy

- 2.12 12. The Non-public Incredulity Fallacy

- 2.13 13. The “No True Scotsman” Fallacy

- 2.14 14. The Ad Hominem Fallacy

- 2.15 15. The Tu Quoque Fallacy

- 2.16 16. The Fallacy Fallacy

- 3 Recognize Logical Fallacies

- 4 How to Monetize a Website: Top Tools & Tips for 2025

- 5 8 Easiest Shared WordPress Web hosting Suppliers in 2023 (When compared)

- 6 Divi Overview: Is It Nonetheless the Very best Multipurpose WordPress Theme To be had in 2022?

0 Comments